2021-01-31

The interview process is an abstraction of what a company believes is important to perform in a particular role. Constructing an interview process is hard for any role. It can be even more difficult for a nascent and broad discipline like product management.

The overall structure and composition of an interview process deserves its own post. For now let’s focus on the first step hiring managers get involved, which is often the phone screen. Candidates have moved past the resume screen and recruiting call at this point. Everything downstream requires time and input from others on the team (e.g. design, engineering, analytics), so this step is meant to produce the most signal with the least effort (i.e. most ROI). The drop-off rates from phone screen to the next stage can range from 60–80% (based on a sampling of companies I have interviewed). Therefore, it is important to get a strong signal. Regardless of company size, this is an important step to get right. For larger organizations with lots of applicants, this is the “quality filter”. For smaller startups with limited time, this is one of the highest leverage activities you can perform to scale the company.

Let’s dive in.

Like any good product manager, we should start with the problem we are trying to solve. What are the goals we are trying to achieve? And what are the non-goals we are willing to sacrifice? This might sound irrelevant but there are many facets to consider. Below is a short list that touches upon the breadth:

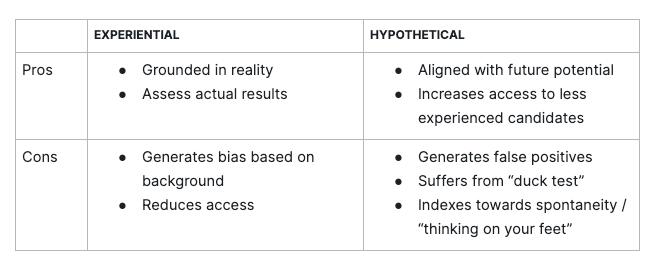

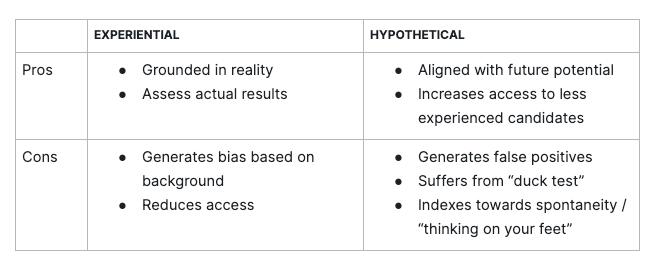

Fortunately, these are not mutually exclusive. But prioritizing one above another will impact the structure of your interview process. Based on my conversations with other product leaders (and my own experience), you end up needing to lean towards proven skill or potential. The two general approaches to assess those attributes are experiential vs hypothetical phone screens. Neither is perfect. Let’s talk about why you might choose one over the other.

The purpose of an experiential interview is to understand how a candidate has actually performed in the past. You are trying to paint a picture of how they approached a problem, how they overcame challenges, how they behaved, how much they individually contributed, and what they learned from it. This is great because it is grounded in reality. Here are a few example questions:

The problem with experiential interviews is that they can inherently cast a bias on the process in two important ways. First, a candidate’s ability to be successful may have been handicapped by being part of a company or team with poor dynamics. Maybe the CEO suffered from “shiny object syndrome”. Maybe their lead didn’t value research and validation. Maybe the company leaned too much on data as the only input. The question you have to answer is whether they were a victim of the situation or a contributing factor.

The second bias is exclusion of candidates with high potential and behavioral excellence, but unproven results. This is a chicken-and-egg problem many face. Should you hire the person who can talk a big game but has never proven they can actually do it? This leads us to the second type of phone screen.

The purpose of a hypothetical question is to understand how a candidate thinks. Your goal is to develop an understanding of their mental models. How do they approach problems? Where do they start? What sort of assumptions do they make? How capable are they of making “good enough” decisions? This is great because it focuses on future potential. Here are a few example questions:

The problem with hypothetical interviews is that they can generate a lot of false positives. There is an old saying, “If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck.” With all the resources available online today, it is easier than ever to quack like a PM. But there is a wide gap between knowing what to say and knowing how to act (in the face of pressure).

If you are hiring for a senior role that will benefit from proven expertise in a specific domain (e.g. navigating a certain regulatory environment), then you may want to lean experiential and be very targeted in your questions. If you are hiring in a space that is less traveled and will benefit from someone who can prove their excellence through mental models (i.e. ways of approaching problems), then you may want to lean hypothetical. And if you have a diverse set of customers, it is always important to remember that a similar representation of diversity within your company will only help in serving them.

The other factor — that will be covered in a future post — is how to structure the rest of the interview process to fill in the gaps from the phone screen. For example, if the rest of the interview process digs into specific project work, then it makes more sense for the phone screen to lean hypothetical. In the end, you need to decide what your primary goal is and what you’re willing to sacrifice.

As much as we don’t want to admit it, interviewing is still more art than science. This tension is perfectly illustrated in this thread between Kaz Nejatian (VP Shopify) and Steven Sinofsky (Partner at a16z and Microsoft legend). Kaz describes one of his favorite screener questions (hypothetical) and Steven challenges the assessment methodology. Both are correct. We’re all just trying to get better.